Hamilton dentist Dr. Steve Tourloukis, who practices Greek Orthodox Christianity, wants to keep his kids in the dark. He has a problem with pluralism, or at least at how it's practiced in his local public schools, and he's filed a lawsuit to try to defend his God-given right to keep his children from learning, well, it would seem pretty much anything he might disagree with.

Hamilton dentist Dr. Steve Tourloukis, who practices Greek Orthodox Christianity, wants to keep his kids in the dark. He has a problem with pluralism, or at least at how it's practiced in his local public schools, and he's filed a lawsuit to try to defend his God-given right to keep his children from learning, well, it would seem pretty much anything he might disagree with.

Supported by a Christian body calling itself the Parental Rights In Education Defense Fund (PRIED), he's claimed in recent news reports that he "is not an extremist" but that he nevertheless "must ensure that (his) children abstain from certain activities that may include lessons which promote views contrary to (his) faith."

Such lessons, according to a September 11 article filed by Toronto Star education reporter Louise Brown, include "topics ranging from homosexuality and birth control to wizardry, evolution, and environmental worship."

One might infer that self-styled non-extremists like Tourloukis seek to challenge comprehensive sex education, Harry Potter novels, and science in one swift stroke while also insinuating that practitioners of earth religions have an agenda to infiltrate public schools.

How ironic. Perhaps, along with J.K. Rowling, he might like to take a stab at Dr. Seuss.

Reactionary, knee-jerk attacks on secular, public education by some conservative Christian groups is nothing new. Never content with the provincially-funded Catholic education system, some factions within the Ontario Christian community tirelessly poke and prod at secular curricula either by attempting to alter classroom activities, institute Christian school prayer, or to (as has been the case with the Durham District School Board) aggressively seek to instill anti-pluralistic candidates in public school trusteeships.

But what makes Tourloukis and PRIED's argument interesting is, in a move one might characterize as the-enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend, the support collected with some Hamilton Muslim families and to issue a "Traditional Values Letter" to seek exclusionary privileges. The Letter, used before by other families during a past swipe against sexual education programs, was drafted by yet another Christian conservative group, Public Education Advocates For Christian Equity (PEACE), who is now supporting Tourloukis in a lawsuit filed against the Hamilton school board.

The "Traditional Values Letter" (circulation of which has been "few in number" according to news reports) requests that "traditional" families with children in public school receive special notification if class lessons involving sex education (including orientation), human evolution, and other activities they deem as "humanist" are part of the curriculum. It also seeks to allow parents to receive a "warning" if lessons "place environmental concerns above the value of Muslim or Christian principles and human life." If so, such parents request the right to have their children excluded from those class activities. And the schools are granting the privilege.

'PRIED' away, as it were, from a complete, inclusive, pluralistic education.

"(Environmental) principles are often presented from a humanistic (for the benefit of man) or a naturalistic world view (deifying the earth)," the Letter asserts, "which is in conflict with our teachings. Conservation (should) be more... connected to... being respectful of their Creator's creation."

Perhaps these folks are unfamiliar with the Song of Solomon. But I digress.

The Letter is a reaction to the Accepting Schools Act, or Bill 13, the pluralism-minded legislation promoting acceptance and diversity in public schools that followed tragic gay-bashing incidents in Ontario and was enacted this year to protect children from bullying. And yes, it was protested by some families who tried to claim that their parental rights were being usurped by the school system. Because, you know, being able to instill bigotry and sexism and homophobia and religious intolerance in children is a parental right. But I digress again.

Bill 13 stipulates that "education plays a critical role in preparing young people to grow up as

productive, contributing and constructive citizens in the diverse

society of Ontario; that all

students should feel safe... and deserve a positive school

climate that is inclusive and accepting, regardless of race, ancestry,

place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual

orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age, marital status,

family status or disability; (that an) inclusive learning environment where all students feel

accepted is a necessary condition... (and) that

students need to be equipped with the knowledge, skills, attitude and

values to engage the world and others critically, which means developing

a critical consciousness [emphasis mine] that allows them to take action on making

their schools and communities more equitable and inclusive for all

people... that a

whole-school approach is required, and that everyone — government,

educators, school staff, parents, students and the wider community — has

a role to play... (and) to assist (students) in developing healthy relationships, making good choices, continuing their learning and achieving success."

"Competing rights can be complex issues," stated Ontario Minister of Education Laurel Broten in a recent Toronto Star report, "(but) a little person can draw a picture of her two Moms or two Dads and feel safe and accepted. That's what happens in classes across Ontario and that's what should happen."

Having finally been thwarted by Bill 13 to insinuate religious doctrines into secular, public education (and despite the argument that Jesus never made a peep about homosexuality in the first place), some conservative Christian groups are now attempting to legally exclude their children from any class activity that, in their view, conflicts with their religious beliefs. Tourloukis and his supporters also seem to be coat-tailing older debates, such as human evolution and those demonically successful Harry Potter novels, in his suit opposing Bill 13. For the people at PRIED, Bill 13 represents "a belligerent government ideology... determined to eradicate all traces of Judeo-Christian morality from society."

And Phil Lees, a former teacher whose so-monickered PEACE group drafted the "Traditional Values Letter", takes the argument a step further, insinuating in recent press reports that its his and Tourloukis' position (supporting the exclusion of children from portions of class curricula), and not that of Bill 13, that is the pluralistic one. In a clever spin that might remind some of "war on Christmas" arguments, Lees stated to the media that "if we're really a public education system, we need to be pluralistic and embrace values that go beyond the humanistic approach of Ontario schools that's based on the belief that there is no spiritual being."

Translation: 'our doctrine defies pluralism and we're arguing for exclusionary privileges in public schools, so the schools' pluralistic and inclusive-oriented legislation deserves to be challenged because now we feel excluded from being able to engage in our anti-pluralism.' Yeah.

For some, withdrawing children from classes that seem problematic to a family might appear to be a common sense approach. If you want to raise your kids within a certain worldview, it certainly seems like a pro-active solution. For many families, this in itself is a key reason to choose homeschooling for one's wee ones, but what if you still intend to send the kids to the local public school? If, as a parent, you do this and wish to see your children acquire an education that trains them to be fully functioning, capable adults, several questions are being begged for.

Why is it, for example, that we never hear stories of outrage from families of other faiths when it comes to school curricula? "I'm sorry, Mrs. Smith, but your class' reading of Orwell's Animal Farm and Golding's Lord Of The Flies is an affront to our family's Quaker principles to non-violence. We must insist that the school remove these titles from your English class reading list immediately." "Mr. Jones, I'm afraid that we must withdraw Sarah from your home economics class because we believe that there aren't sufficient kosher provisions within the curriculum and we believe that exposure to anything treif will only confuse her."

Could it be because most people have the common sense to recognize that secular, postmodern Western life is teeming with messages and influences of all kinds, and that their family's spirituality is something they can and do enjoy without feeling thwarted by global diversity of thought? Or is it simply that they practice a doctrine that doesn't include the anti-social, often violently presumptive insistence that everyone else on the planet amend their ways to suit their whimsy? Exactly how weak does one's participation in a belief system have to be in order to take a "conflicting" point of view as an affront?

Frequently, these voices attempt to argue for an apparent supremacy in public consciousness to hegemonize their own worldview. We see this by the use of the term "traditional," applied as a conceptual weapon to undermine the values of other points of view. If it's "traditional," we're taught to accept, it must be "good," or more to the desired point, "right."

Perhaps it is time to re-examine the use of the term "traditional values."

Arguably, the LGBT community's struggle toward acceptance, same-sex marriage, and equal protection is this decade's civil rights movement. Reactionary groups, almost exclusively Christian-based, cite terms like "traditional marriage" and "traditional values" to support their arguments against this.

If we're going to accept terms like "traditional," meaning something

old, historic, the-way-things-get-done as a legitimizing quotient to

support the supremacy of an act or idea, then what if society also explored stepping back to, say, "traditional employment" such as child

labour or even black slavery, or "traditional medicine" including leech bleeding and trepanning? Surely, the traditional-values person might also find equal and preferred legitimacy in these approaches, no?

Anthropologists will demonstrate that, in cultures, a thing becomes a tradition when, over time, a body of habits or practices continue over several generations because of meanings or beliefs attributed to them have persisted within a community. But for this to be so, for a tradition to ultimately persist, participation must ultimately be voluntarily accepted. The meanings behind a tradition must continue to remain relevant and useful and desired-for among individual to individual over time, or else the tradition will have to face change in the wake of new and different ideas. A tradition can be forcibly imposed however, but then the very act of imposing a tradition demonstrates that the principles behind the tradition were already being challenged by those who are influenced by it. To forcibly impose a tradition is to illustrate its impermanence.

Meanwhile, in Quebec, Catholic parents have attempted to exclude their children from classes that taught about

other religions. Arguing that these programs "interfered with their ability

to pass on the Catholic religion to their children," and that "exposing

their children to various religions was confusing," they claimed

their children would suffer "serious harm from contact with a series of

beliefs that were mostly incompatible with those of the family." The Supreme Court of Canada ruled against them.

In Brampton, student Jonathan Erazo is currently being denied exemption from religious studies courses at Notre Dame Catholic Secondary School since making his choice to break away from the Catholic faith. Claiming "denominational rights," the school and its board are refusing the request, filed by Erazo's parents.

There is an expectation, the Quebec school officials reply, that students enrolling within the Catholic school board system attend faith-based courses, regardless of whether such students are practicing Catholics or not, even if members of other faiths.

Christian schoolchildren in Ontario may be removed from science,

biology, and English classes if the topics are deemed offensive by their

parents, but non-Catholic schoolchildren in Quebec are not extended the

same option when it comes to religious studies classes.

"It's part and parcel of coming to a faith-based school," stated Dufferin-Peel Catholic District School Board spokesman Bruce Campbell in recent media reports.

Is it then unreasonable for Christian families in Ontario to expect that a fully secular education, including comprehensive sex education, human evolution, and popular literature that has a proven track record to encourage children to read is part and parcel of coming to a public-based school?

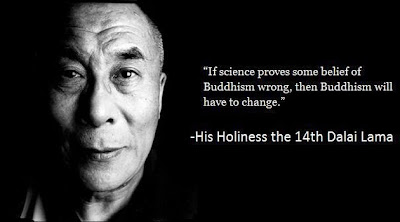

But, in the end, when all the debates about "denominational rights" or "environmental worship" or humanism or pluralism are said and done, there is one cornerstone that remains unarguably fundamental to what people like Tourloukis and Lees are advocating, and that is the right to hamstring their children. By seeking to prevent them from being fully immersed in what contemporary education systems can offer, with all of society's developments in science and literature and everything else that is available to learn in the 21st century, they are guaranteeing that their children will not be as aware, prepared, and sophisticated as their peers when they reach adulthood.

These voices are arguing in support of ignorance.

Whether homeschooled or as a part of an education system, any person lacking in any field of knowledge will ultimately find him- or herself at a disadvantage. Tourloukis styles himself as a "not an extremist," but the intent to knowingly so control a child's awareness of the world defies that description, especially since it's ultimately doomed to failure. That same child is bound to socialize with class peers who were present during those allegedly offensive classes, and sooner or later is going to ask or hear about what was missed. There will likely be some exam or quiz that covered the heinous material. And even if that child is "successfully" "saved" from being exposed to such heretical thinking in that class on that day, that doesn't mean that this child isn't going to see or hear or experience something else through reading, or pop culture, or being on the internet, or even overhearing a conversation between strangers while riding the bus on the way to Sunday school.

So, if you're a conservative, "traditional values" sort of Christian parent who feels slighted and thwarted by the "humanist," pluralistic, inclusive-minded path that public schools take, what are your options? What to do?

You could always be thankful that, as a result of the weird history of Canadian colonization, the government offers you a funded Catholic school board system. No other religious community in the country can claim such a privilege, and (pardon the expression) God knows many of them would love to. And if this Catholic system isn't "Christian enough" for you, well, suck it up.

Or, if you really feel ambitious, feel free to homeschool your kids. Just know that if you do, you might well feel completely pleased with yourself that you "rescued" your children from the "evils" of society, but you may have also managed to stunt their awareness, and possibly even their sense of compassion and other social skills, by excluding their consciousness to the workings of the rest of the world.

For any family, the merits of a religious upbringing will become apparent as a child grows to adulthood. If a religious life is healthy and positive in that family, religious teachings will likely thrive and continue on its own merits regardless of what other ideas or concepts a person might be exposed to throughout one's life. Many families manage to live religiously, and happily so, in a world where contradictory messages are abundant; those who attempt to control what outside ideas may or may not influence people only demonstrate their own insecurity at the questioning of their predisposed ideas. They fall back on terms like "traditional" to assert a sense of supremacy in a world that, like it or not, is becoming more and more pluralistic and multicultural and, yes, humanist.

The days of Christian hegemony are long over. Still, Christianity survived Galileo's realization that the sun was the center of the universe, and it will survive this decade's growing movement toward acceptance and inclusivity of the queer populace. Just as racist and anti-Semitic Christian "Identity" churches are regarded as extreme and illegitimate by most religious people in 2012, the time will come when the same will be said for general Christian relations toward homosexuals. Or people who read Scientific American more frequently than the King James Bible. Or who think being in an old-growth forest can be a spiritual experience. Or believe that just because their kids understand that the human species evolved over time from other bipedal creatures hundreds of thousands of years ago, that doesn't have to conflict with the idea that life is a glorious experience worthy of sacred celebration and humbling respect.